Journal Contents

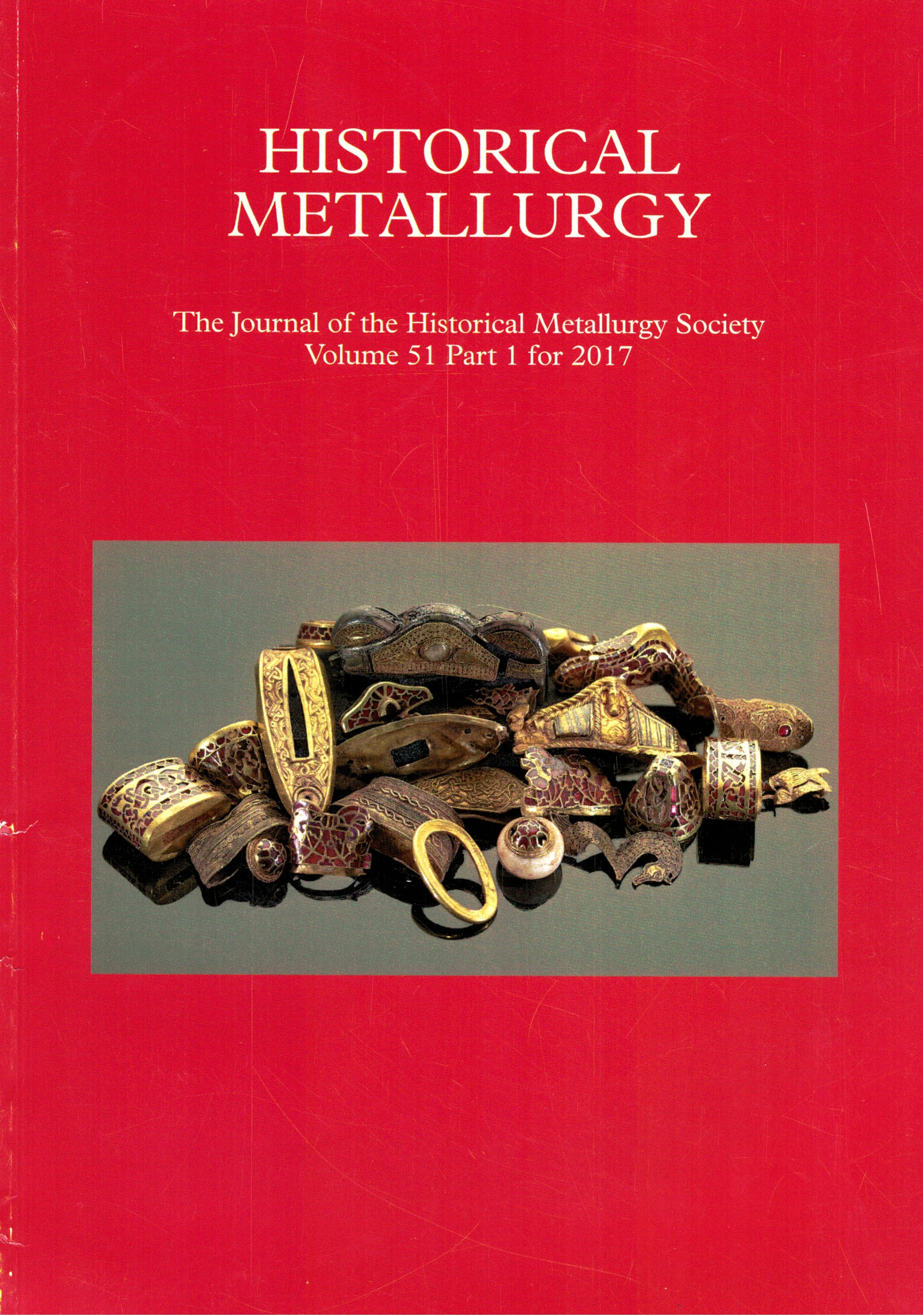

Recycling in the Saxon period: results from the metals analysis of the Staffordshire Hoard

Eleanor Blakelock

Pages 1-12

The Staffordshire Hoard is the largest single find of Anglo-Saxon material found in England to date. It represents the warrior elite, is dated to the Early Saxon period and consists of gold and silver items, mostly weapon fittings, with a few copper alloy cores. The metals in the Hoard were examined as part of a much larger research project. The composition of the gold was examined using scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray analysis (SEM-EDX); X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was used to examine the silver and copper alloys. The results suggest the gold and silver alloys are either mixed or recycled. The copper alloys appear to be tin bronzes, which seems to contradict other copper alloy studies of this period. The compositions of the three alloys are however fairly consistent, suggesting that even if recycled the alloy composition was potentially being controlled by the metal smith.

Smithies and forges around the north-eastern Baltic Sea from the 11th to the 17th century AD

Ragnar Saage

Pages 13-21

This study focuses on smithy and forge constructions in present day Estonia and Finland. The studied smithies can be divided into three time periods: pre-crusade Late Iron Age (11th–12th centuries); the age of transition (13th and 14th centuries), when foreign craftsmen settled in newly founded towns bringing their own traditions; and the 15–17th centuries, during which rivalry was established between rural and urban smiths. The most visible feature in the smithies – the forge – also changed during this period, evolving from a ground-level forge pit into a massive rectangular raised forge. The latter was adopted following the crusades and continued to be used until the 19th century.

The performance of Abraham Darby I’s coke furnace revisited, part 1: Temperature of operation

Richard Williams

Pages 22-33

Abraham Darby I’s coke-fired furnace produced a higher-silicon iron than prior charcoal ones, which was critical for the casting of thin pots in sand. This silicon content has hitherto been attributed to an enforced higher temperature of operation with coke. This paper sets out to show that there were other reasons why coke iron had a higher silicon content than charcoal iron, and that the temperature in his hearth was probably no higher than that in a charcoal furnace. The causes of high silicon content in coke iron were the higher density of coke, leading to a longer dwell time, and the now-appreciated effect of reactive silica in the coke, not present in charcoal. The paper suggests that the breakthrough by Abraham Darby II that led to coke iron being fit for the forges was the removal of sulphur by using higher temperatures in bigger furnaces.

The refining process, part 2: new data from Ynysfach Ironworks, Merthyr Tydfil

Tim Young and Rowena Hart

Pages 34-50

Refining was an intermediate process for conversion of the grey cast iron produced by the smelting of, principally Coal Measures, iron ore into a white cast iron known as finers metal that was suitable for conversion to wrought iron by puddling. It was adopted first in Merthyr Tydfil in 1791, following the failure of Cort’s puddling process to produce good iron directly from coke pig. Refining entailed the remelting of the pig iron under strongly oxidising conditions, followed by rapid chilling of the iron. Archaeometallurgical analysis of samples from excavation of the 1830s–1870s refinery building of the Ynysfach Ironworks, Merthyr Tydfil, has permitted the first modern reappraisal of the refining process. The residues possessed a very high phosphorus content which generated an unusual mineralogy, including phosphoran varieties of the minerals olivine and iscorite. Dephosphorisation was a major function of refining.

![[Test] The Historical Metallurgy Society](https://test.historicalmetallurgy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Logo120.png)

There are no reviews yet.